By: David Barton

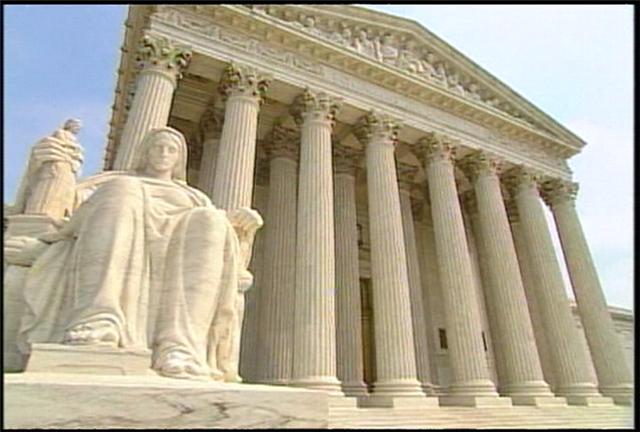

WallBuilders

The Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges that established homosexual marriage as national policy is unambiguously wrong on at least three crucial levels: Moral, Constitutional, and Structural.

On the Moral Level

The Court’s decision violates the moral standards specifically enumerated in our founding documents. The Declaration of Independence sets forth the fundamental principles and values of American government, and the Constitution provides the specifics of how government will operate within those principles. As the U. S. Supreme Court has correctly acknowledged:

The latter [Constitution] is but the body and the letter of which the former [Declaration of Independence] is the thought and the spirit, and it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. [1]

The Declaration first officially acknowledges a Divine Creator and then declares that America will operate under the general values set forth in “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.” The framers of our documents called this the Moral Law, and in the Western World it became known as the Common Law. This was directly incorporated into the American legal system while the colonies were still part of England; [2] following independence, the Common Law was then reincorporated into the legal system of all the new states to ensure its uninterrupted operation; [3] and under the federal Constitution, its continued use was acknowledged by means of the Seventh Amendment in the Bill of Rights. Numerous Founding Fathers and legal authorities, including the U. S. Supreme Court, affirmed that the Constitution is based on the Common Law, [4] which incorporated God’s will as expressed through “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.” [5]

Those constitutional moral standards placed the definition of marriage outside the scope of government. As acknowledged in a 1913 case:

Marriage was not originated by human law. When God created Eve, she was a wife to Adam; they then and there occupied the status of husband to wife and wife to husband. . . . It would be sacrilegious to apply the designation “a civil contract” to such a marriage. It is that and more – a status ordained by God. [6]

Because marriage “was not originated by human law,” then civil government had no authority to redefine it. The Supreme Court’s decision on marriage repudiates the fixed moral standards established by our founding documents and specifically incorporated into the Constitution.

On the Constitutional Level

The Constitution establishes both federalism and a limited American government by first enumerating only seventeen areas in which the federal government is authorized to operate, [7] and then by explicitly declaring that everything else is to be determined exclusively by the People and the States (the Ninth and Tenth Amendments).

Thomas Jefferson thus described the overall scope of federal powers by explaining that “the States can best govern our home concerns and the general [federal] government our foreign ones.” [8] He warned that “taking from the States the moral rule of their citizens and subordinating it to the general authority [federal government] . . . . would . . . break up the foundations of the Union.” [9] The issue of marriage is clearly a “domestic” and not a “foreign” issue, and one that directly pertains to the State’s “moral rule of their citizens.” But the Supreme Court rejected these limits on its jurisdiction, and America now experiences what Jefferson feared:

[W]hen all government, domestic and foreign, in little as in great things, shall be drawn to Washington as the center of all power, it will render powerless the checks provided of one government on another. [10]

By taking control of issues specifically delegated to the States, the Court has disregarded explicit constitutional limitations and directly attacked constitutional federalism.

On the Structural Level

The Constitution stipulates that “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a republican form of government” (Article IV, Section 4). A republican form of government is one in which the people elect leaders to make public policy, with those leaders being directly accountable to the people. More than thirty States, by their republican form of government, had established a definition of marriage for their State. The Supreme Court decision directly abridges the constitutional mandate to secure to every state a republican form of government.

To believe that the Judiciary is an independent and neutral arbiter without a political agenda is ludicrous. As Thomas Jefferson long ago observed:

Our judges are as honest as other men and not more so. They have, with others, the same passions for party, for power, and the privilege of their corps. [11]

Judges definitely do have political views and personal agendas; they therefore were given no authority to make public policy. The perils from their doing were too great. As Jefferson affirmed, the judges’ “power [is] the more dangerous as they are in office for life and not responsible, as the other functionaries are, to the elective control.” [12] He therefore warned:

[T]o consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [is] a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy. . . . The Constitution has erected no such single tribunal. [13] The Constitution, on this hypothesis, is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the Judiciary which they may twist and shape into any form they please. [14]

The Supreme Court’s decision is a direct assault on the republican form of government that the Constitution requires be guaranteed to every State.

The Road Ahead

The Supreme Courts decree on marriage will become a club to bludgeon the sincerely-held rights of religious conscience, especially of those in the several dozen States who, through their republican form of government, had enacted public policies that conformed to both the Moral Law and the traditional Common Law.

While the Supreme Court decision paid lip service to the rights of religious people to disagree with its marriage decision, history shows that not only does this acknowledgment mean little but also that it will be openly disregarded and ignored, particularly at the local level. After all, there are numerous Supreme Court decisions currently on the books – including unanimous Court decisions – protecting the rights of religious expression in public, including for students. Yet such faith expressions continue to be relentlessly attacked by school and city officials at the local and city levels. (See www.religioushostility.org for thousands of such recent examples.)

Even before this decision was handed down, numerous States were already punishing dissenting people of faith, levying heavy fines on them or closing their businesses – not because those individuals attacked gay marriage but rather because they refused to personally participate in its rites. These governmental actions were initiated by complaints of homosexuals filed with civil rights commissions – and all of this was already occurring without a Supreme Court decision on which they could rely. Now that such a decision does exist, expect a tsunami of additional complaints to be filed against Christian business owners, and both the frequency and the intensity of the penalties to be increased.

Now is the time to display stand-alone courage on the issue of marriage as well as the judicial activism of the Court – now is the time to stand up and be counted, regardless of whether anyone else stands with you. Now is the time for individuals to broadly voice support for traditional marriage (which will likely cause you to be verbally berated or attacked by its opponents) as well as for the rights of religious conscience of dissenters (which will cause you to be charged with defending bigots and haters). Good people can no longer be silent and allow themselves to be intimidated by the mean-spirited attacks that occur when you begin to speak out on this issue.

It will soon become obvious that this decision opened a Pandora’s Box that will initiate a series of policy changes affecting everything from hiring practices to college athletics, from non-profit tax-exempt status to professional licensing standards. So the battle is not over; it is literally just beginning. We have a duty to let our voice be heard.

Strikingly, duty was the character trait of Jesus. He loved us because it was the right thing to do; He went to the cross because it was the right thing to do; He forgave us because it was the right thing to do. It was His duty. Our Founders repeatedly praised that character trait, and noted the numerous spiritual blessings that came from its performance:

The man who is conscientiously doing his duty will ever be protected by that Righteous and All-Powerful Being, and when he has finished his work, he will receive an ample reward. [15] Samuel Adams, signer of the declaration

All that the best men can do is to persevere in doing their duty . . . and leave the consequences to Him who made it their duty, being neither elated by success (however great) nor discouraged by disappointment (however frequent and mortifying). [16] John Jay, original chief justice of the u. s. supreme court, author of the federalist papers

The sum of the whole is that the blessing of God is only to be looked for by those who are not wanting in the discharge of their own duty. [17] John Witherspoon, Signer of the Declaration

People of faith need to regain the concept of duty, and we would do well to adopt the motto that characterized the efforts of Founding Father John Quincy Adams: “Duty is ours, results are God’s.” [18] Now is the time for people of faith to be silent no more.

[1] Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway Company v. Ellis, 165 U. S. 150, 160 (1897).

[2] Zephaniah Swift, A System of the Laws of the State of Connecticut (Windham: John Byrne, 1795), Vol. I, pp. 1-2, “Of Law and Government;” Henry Campbell Black, A Law Dictionary Containing Definition of the Terms and Phrases of American and English Jurisprudence, Ancient and Modern (St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1910), pp. 226-227, s.v. “common law;” John Bouvier, Law Dictionary, Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America, and of the Several States of the American Union (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1892), Vol. I, pp. 348-349; Alexander M. Burrill, A Law Dictionary and Glossary (New York: Baker, Voorhis & Co., 1867), Vol. I, pp. 324-326.

[3] Zephaniah Swift, A System of the Laws of the State of Connecticut (Windham: John Byrne, 1795), Vol. I, pp. 1-2, “Of Law and Government;” Henry Campbell Black, A Law Dictionary Containing Definition of the Terms and Phrases of American and English Jurisprudence, Ancient and Modern (St. Paul: West Publishing Co., 1910), pp. 227-227, s.v. “common law;” John Bouvier, Law Dictionary, Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America, and of the Several States of the American Union (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1892), Vol. I, pp. 348-349; Alexander M. Burrill, A Law Dictionary and Glossary (New York: Baker, Voorhis & Co., 1867), Vol. I, pp. 324-326.

[4] See, for example, U.S. v. Coolidge, 1 Gall. 488 (1813); U.S. v. Wonson, 1 Gall. 5 (1812); Robinson v. Campbell, 16 U.S. 3 Wheat. 212 (1818); Alexander M. Burrill, A Law Dictionary and Glossary (New York: Baker, Voorhis & Co., 1871), Vol. I, pp. 324-326; Thomas M. Cooley, A Treatise on the Constitutional Limitations which Rest Upon the Legislative Power of the States of the American Union (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1871), pp. 21-25, “The Formation and Amendment of State Constitutions”; Theron Metcalf & Jonathan Perkins, Digest of the Decisions of the Courts of Common Law and Admiralty in the United States (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1860), Vol. I, p. 532, s.v. “common law”; John Bouvier, Law Dictionary, Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America, and of the Several States of the American Union (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1892), Vol. I, pp. 348-349; etc.

[5] See, for example, Alexander M. Burrill, A Law Dictionary and Glossary (New York: Baker, Voorhis & Co., 1867), Vol. I, p. 325; A. J. Dallas, Reports of Cases Ruled and Adjudged in the Several Courts of the United States and of Pennsylvania Held at the Seat of the Federal Government (Philadelphia: J. Ormrod, 1799), Vol. III, p. 139, Talbot, Appellant, versus Janson, Appellee, et al. which says: “But the abstract right of individuals to withdraw from the society of which they are members, is recognized by an uncommon coincidence of opinion – by every writer, ancient and modern; by the civilian, as well as by the common-law layer; by the philosopher, as well as the poet: It is the law of nature, and of nature’s god, pointing to ‘the wide world before us, where to chuse our place of rest, and providence our guide’;” Giles Jacob, A New Law Dictionary (New York: Frederick C. Brightly, 1905), s.v. “Common Law” which says: “The common law is grounded upon the general customs of the realm; and includes in it the Law of Nature, the Law of God, and the Principles and Maxims of the Law: It is founded upon Reasons; and is said to be perfection of reason, acquired by long study, observation and experience, and refined by learned men in all ages”; Giles Jacob & T. E. Tomlins, The Law-Dictionary: Explaining the Rise, Progress, and Present State of the English Law (Philadelphia: Fry and Kammerer, 1811), Vol. IV, p. 89, s.v. “law” which says: “The law of nature is that which God at mans’ creation infused into him, for his preservation and direction; and this is lex eterna and may not be changed: and no laws shall be made or kept, that are expressly against the Law of god, written in his Scripture; as to forbid what he commandeth, & c. 2 Shep. Abr. 356”; William Nicholson, American Edition of the British Encyclopedia or Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (Philadelphia: Mitchell, Ames, and White, 1821), Vol. VII, s.v. “Law” which says “But this large division may be reduced to the common division; and all is founded on the law of nature and reason, and the revealed law of God, as all other laws ought to be”; Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (Boston: Hillard, Gray, and Company, 1833), Vol. III, p. 724, § 1867; Testimony of Distinguished Laymen to the Value of the Sacred Scriptures (New York: American Bible Society, 1854), pp. 51-53, Justice John McLean, November 4, 1852. See also Samuel W. Bailey, Homage of Eminent Persons to the Book (New York, 1869), p. 54, Joseph Hornblower, chief justice of New Jersey; Updegraph v. The Commonwealth, 11 S. & R. 394, 399 (Sup. Ct. Pa. 1824); Richmond v. Moore, 107 Ill. 429, 1883 WL 10319 (Ill.), 47 Am.Rep. 445 (Ill. 1883); State v. Mockus, 14 ALR 871, 874 (Maine Sup. Jud. Ct., 1921); Cason v. Baskin, 20 So.2d 243, 247 (Fla. 1944) (en banc); Stollenwerck v. State, 77 So. 52, 54 (Ala. Ct. App. 1917) (Brown, P. J. concurring); Gillooley v. Vaughn, 110 So. 653, 655 (Fla. 1926), citing Theisen v. McDavid, 16 So. 321, 323 (Fla. 1894); Rogers v. State, 4 S.E.2d 918, 919 (Ga. Ct. App. 1939); Brimhall v. Van Campen, 8 Minn. 1 (1858); City of Ames v. Gerbracht, 189 N.W. 729, 733 (Iowa 1922); Ruiz v. Clancy, 157 So. 737, 738 (La. Ct. App. 1934), citing Caldwell v. Henmen, 5 Rob. 20; Beaty v. McGoldrick, 121 N.Y.S.2d 431, 432 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1953); Ex parte Mei, 192 A. 80, 82 (N.J. 1937); State v. Donaldson, 99 P. 447, 449 (Utah 1909); De Rinzie v. People, 138 P. 1009, 1010 (Colo. 1913); Addison v. State, 116 So. 629 (Fla. 1928); State v. Gould, 46 S.W.2d 886, 889-890 (Mo. 1932); Doll v. Bender, 47 S.E. 293, 300 (W.Va. 1904) (Dent, J. concurring); and many others. See, also, Joseph Story, A Discourse Pronounced upon the Inauguration of the Author, as Dane Professor of Law in Harvard University, on the Twenty-Fifth Day of August, 1829 (Boston: Hilliard, Gray, Little, and Wilkins, 1829), pp. 20-21; John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1851), Vol. III, p. 439, “On Private Revenge,” originally published in the Boston Gazette, September 5, 1763; James Wilson, The Works of the Honourable James Wilson, Bird Wilson, editor (Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press, 1804), Vol. I, p. 104, “Of the General Principles of Law and Obligation”; Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U.S. 457, 470-471 (1892); Shover v. State, 10 Ark. 259, 263 (1850); People v. Ruggles, 8 Johns 225 (1811); Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821, assembled for the purpose of amending the Constitution of the State of New York, Nathaniel H. Carter and William L. Stone, reporters (Albany: E. and E. Hosford, 1821), p. 576, October 31, 1821; Charles B. Galloway, Christianity and the American Commonwealth (Nashville: Publishing House Methodist Episcopal Church, 1898), pp. 170-171; Lindenmuller v. The People, 33 Barb 548, 560-564, 567 (Sup. Ct. NY 1861); Strauss v. Strauss, 148 Fla. 23, 3 So.2d 727 (Sup.Ct.Fla. 1941); and many others.

[6] Grigsby v. Reib, 153 S.W. 1124, 1129-30 (Tex.Sup.Ct. 1913).

[7] Article I, Section 1 lists fifteen powers permissible to the federal government; two additional federal powers are added through constitutional amendments, thus bringing the total number of constitutionally-authorized federal jurisdictions to seventeen.

[8] Thomas Jefferson, Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies, From the Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, editor (Boston: Gray and Bowen, 1830), Vol. IV, p. 374, to Judge William Johnson on June 12, 1823.

[9] Thomas Jefferson, Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies, From the Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, editor (Boston: Gray and Bowen, 1830), Vol. IV, p. 374, to Judge William Johnson on June 12, 1823.

[10] Thomas Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D. C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, p. 332, to Charles Hammond on August 18, 1821.

[11] Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D. C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, p. 277, to William Charles Jarvis on September 28, 1820.

[12] Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D. C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, p. 277, to William Charles Jarvis on September 28, 1820.

[13] Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D. C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, p. 277, to William Charles Jarvis on September 28, 1820.

[14] Thomas Jefferson, Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington D. C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, p. 215, to Judge Spencer Roane on September 6, 1819.

[15] Samuel Adams, The Writings of Samuel Adams, Harry Alonzo Cushing, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907), Vol. III, to Mrs. Adams on January 29, 1777.

[16] John Jay, The Life of John Jay: With Selections from His Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers, William Jay, editor (New York: J & J Harper, 1833), Vol. II, p. 174, to the Reverend Richard Price on September 27, 1785.

[17] John Witherspoon, Dominion of Providence Over the Passions of Men. A Sermon Preached at Princeton on the 17th of May, 1776. Being the General Fast Appointed by the Congress Through the United Colonies (Philadelphia: 1777), p. 32.

[18] Elbridge S. Brooks, Historic Americans: Sketches of the Lives and Characters of Certain Famous Americans (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, 1899), p. 209.