By: James Simpson | Capital Research Center

Summary: A vast network of foundations, non-profits, government entities and political organizations have a vested interest in the continued growth of the resettlement of refugees in America. Because they receive billions of dollars in federal grant money, publicly-financed, tax-exempt organizations have significant incentives to support political candidates and parties that will keep these programs alive. These organizations need to be thoroughly audited and the current network of public/private immigrant advocacy and resettlement organizations needs to be completely overhauled. Resettling refugees should be a voluntary, genuinely charitable activity, removing all the perverse incentives government funding creates.

Who is eligible for resettlement?

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS), refugees are:

[P]eople who have been persecuted or fear they will be persecuted on account of race, religion, nationality, and/or membership in a particular social group or political opinion.

This mirrors the U.N. definition established at the 1951 U.N. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. It is important to note here, however, that under these definitions, “individuals who have crossed an international border fleeing generalized violence are not considered refugees.” This includes large numbers of people who are regularly resettled anyway, for example, some of the Syrians fleeing that country’s conflict, and most—if not all Somalis.

Those who meet the definition include:

- refugees (those seeking protection in the United States who are not already in the country),

- asylum seekers or asylees (those who apply for asylum after coming to the U.S.),

- Cuban/Haitian Entrants,

- Special Immigrant Visas (SIV) and

- trafficking Victims.

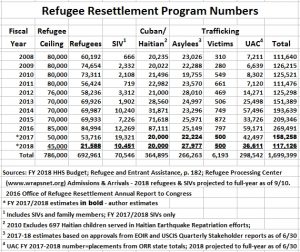

The Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC) program is also administered by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, although UACs do not meet the definition of “refugee.” Table I below provides up-to-date estimates for each category.

Table I

A few particulars are worth mentioning. First, refugee numbers have declined dramatically. In 2018, they reached the lowest numbers since the program began.

Asylum cases have, if anything, increased, and while Unaccompanied Alien Children numbers are down somewhat this year, they still remain historically high. Overall, the whole program is just now reaching pre-Obama levels.

The Cuban/Haitian Entrant Program (CHEP), was created by the Refugee Education Assistance Act of 1980 in response to the Mariel Boat Lift, when 125,000 Cubans and over 40,000 Haitians attempted to immigrate en masse by boat to the U.S. It is a form of humanitarian parole, which allows entry of otherwise inadmissible aliens for humanitarian reasons. CHEP offers benefits to Cubans and Haitians on par with other refugee groups. As part of this, the so-called “wet foot-dry foot” policy provided expedited permanent residence status to Cubans who successfully reached American shores (dry-foot). If intercepted by U.S. authorities at sea, (wet-foot), they would be returned to Cuba. CHEP is managed by Church World Service and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops with funding provided by the Office of Refugee Resettlement and USCIS.

Just a few days prior to leaving office in 2017, President Obama cancelled wet-foot-dry foot. This change was made as part of President Obama’s normalization of relations with Communist Cuba, and the numbers of people fleeing Cuba soared in 2015-2016 in anticipation. There are still Program-eligible Cubans and Haitians, but the numbers down substantially since the end of wet foot-dry foot. As there are no current published numbers for 2017-18, estimates provided are a rough guess. Ending this policy put Cuban and Haitian immigrants on a level playing field with all other refugee groups and ended the incentive for Cubans to risk their lives on a dangerous sea-crossing to America. With the exception of the Vietnamese Boat People (also fleeing a communist regime), few groups other than the Cubans have gone to such extraordinary lengths over so many years to escape an oppressive government.

Asylum is broken down into two categories: affirmative and defensive. Affirmative asylees are those who formally apply for asylum status at our nation’s borders. Defensive asylees are people in deportation proceedings who request asylum status to avoid deportation. Affirmative asylum cases are decided by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; the U.S. Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review decides defensive asylum cases.

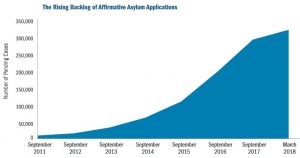

Asylum applications have exploded in recent years, as shown in the above chart of affirmative case backlogs. As of March 31, 2018, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ affirmative asylum backlog was 318,624. The EOIR backlog, which includes defensive asylum and other types of deportation cases, was 732,730 as of June 30.

The Special Immigrant Visa program (SIV) awards refugee status to Iraqis and Afghanis who have helped the U.S. military as interpreters and translators during military operations in those countries. Many of these individuals legitimately face the threat of death if they remain in their own countries. In recent years, their numbers have also soared.

Voluntary Agencies

The Voluntary Agencies or VOLAGs are private, tax-exempt organizations that resettle refugees for the U.S. government. There are nine VOLAGs, six of which are nominally religious, and these organizations often promote their resettlement activity as a biblical mission. However, VOLAGs are strictly prohibited by regulation from any form of proselytization to refugees. In reality, they are simply government contractors paid handsomely for their services. The VOLAGs are:

-

- Church World Service (CWS);

- Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church (DFMS), also called Episcopal Migration Ministries;

- Ethiopian Community Development Council (ECDC);

- HIAS, Inc, (formerly Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society);

- International Rescue Committee (IRC);

- Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS);

- U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB);

- U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI);

- World Relief Corporation of the National Association of Evangelicals (WRC).

VOLAGs utilize a network of about 300 subsidiaries called “affiliates” who perform most of the actual resettlement work. This includes providing the following services to refugees for the first 30-90 days of their resettlement in the U.S.:

- Decent, safe, sanitary, affordable housing in good repair

- Essential furnishings

- Food, food allowance

- Seasonal clothing

- Pocket money

- Assistance in applying for public benefits, social security cards, ESL, employment services, non-employment services, Medicaid, Selective Service

- Assistance with health screenings and medical care

- Assistance with registering children in school

- Transportation to job interviews and job training

- Home visits

The VOLAGs work the administrative end, distributing federal resettlement dollars and deciding where to relocate the refugees. It is also important to note that refugees get priority for housing. As a result, many Americans go homeless or are otherwise denied public housing for extended periods. In New Hampshire, for example, where refugee resettlement has stressed many communities to the breaking point, the wait time for public housing is eight years.

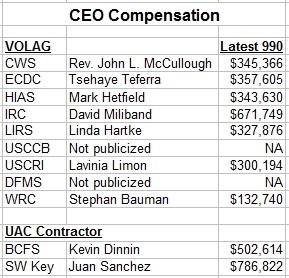

Table II

The two main UAC resettlement contractors are Baptist Child and Family Service (BCFS), and Southwest Key Programs (SW Key), but many others are involved in this lucrative business. More about that later.

VOLAG and UAC contractor leaders do very well by doing good. Table II lists the CEO compensation of the VOLAGS and main UAC contractors, as available. This information is provided on the IRS Form 990 non-profit annual tax return most of them must file. It is important to note that, while substantial, these salaries would not normally be out of line for a corporate CEO. But these are tax-exempt entities that merely administer federal grants. They are little more than glorified clerks.

In the conclusion of Resettling Refugees, find out how many private nonprofit groups depend on government programs in order to stay in operation.