By: Denise Simon | Founders Code

Three separate shipments full of parts were intercepted in recent weeks, according to law enforcement sources familiar with the matter, and were packed in their own cargo containers on three separate ships that were also carrying household items, apparel, toys, industrial machinery, and other imports.

With a Domestic Value of over $378,000 the seized items were found in violation of the Chinese Arms Embargo

LOS ANGELES — U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) at Los Angeles/Long Beach Seaport in coordination with the Machinery Center of Excellence and Expertise (CEE), and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), intercepted and seized 52,601 firearms parts in violation of the Chinese Arms Embargo. The seized items described as sights, stocks, muzzles, brakes, buffer kits, and grips which arrived in three shipments from China, had a combined domestic value of $378,225.00.

CBP officers referred the items to ATF investigators, who confirmed that the firearm parts were in violation of the Arms Export Control Act and International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), 27 CFR 447.52.

“This seizure is an exceptional example of CBP officers and import specialists vigilance, commitment and keen focus in enforcing complex arms embargo regulations,” said Carlos C. Martel, CBP Director of Field Operations in Los Angeles. “The Chinese Arms Embargo is just one of the hundreds of regulations CBP enforces, ensuring the safety and security of our country.”

Federal regulations impose importation restrictions to certain countries to which the United States maintains an arms embargo, and one of such countries is China.

“We work closely with our strategic partners to ensure import compliance while maintaining the highest standards of security at our nation’s largest seaport,” remarked LaFonda Sutton-Burke, CBP Port Director of the LA/Long Beach Seaport. “This interception underscores the successful collaboration between CBP officers, import specialists, and ATF investigators.” In fiscal year (FY) 2018, Office of Field Operations (OFO) seized 266,279 firearms, firearm parts, ammunition, fireworks and explosives at 328 ports of entry throughout the United States. These interceptions represent an increase of 18.4 percent from the previous year.

Gotta wonder what led to this. Consider if this is related. Just 2 months ago…

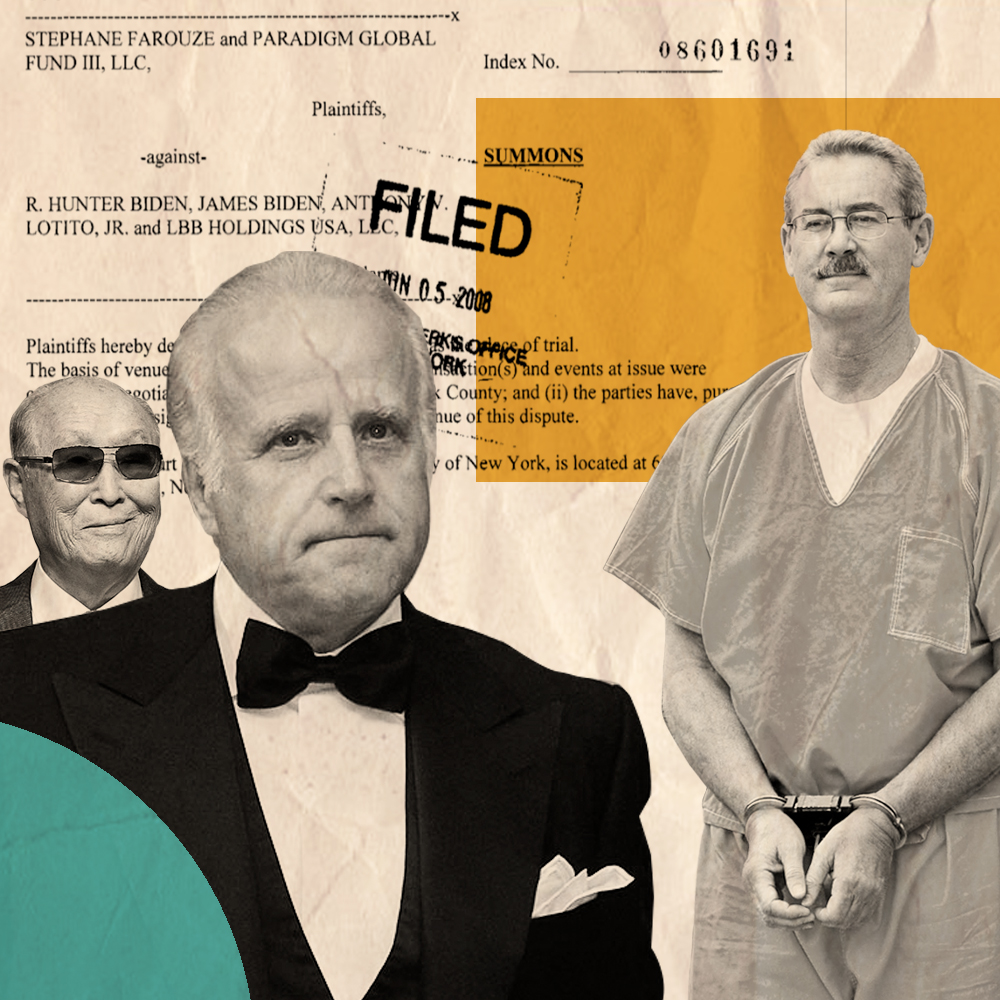

When federal agents raided the Southern California home of US Customs and Border Protection supervisor Wei “George” Xu in February, they seized an arsenal of more than 250 weapons, including nearly three dozen illegal machine guns, according to court records.

“Weapons of war,” a prosecutor would later call them.

Xu, 56, was arrested and charged with dealing firearms without a license. He has pleaded not guilty.

But guns are not the reason the veteran officer has been held without bond since his arrest four months ago.

Instead, the Chinese-born naturalized US citizen has remained behind bars amid concerns about his secret-level security clearance and what prosecutors described as “highly suspicious” contacts with Chinese consular officials in Los Angeles.

Prosecutors are also examining the apparent gulf between Xu’s estimated $120,000-to-$130,000 salary as a federal law enforcement officer and his “luxurious lifestyle,” in which he drove a Maserati, went on big game hunting trips to Africa and had approximately $1.4 million in the bank, according to court records. The cache of weapons recovered from Xu’s house was estimated to be worth more than $200,000, according to prosecutors. Additionally, prosecutors allege that Xu and his wife failed to report several years of income from a rental property they’ve owned since 2015.

Xu’s defense attorney, Mark Werksman, said in court papers that his client has lived in the United States for three decades, has no previous criminal record, and, because his passport was seized as part of the investigation, has no ability to travel outside the country.

The lawyer was unsuccessful, however, in his attempt to convince a federal judge at a hearing last month that Xu could be trusted to show up for trial if he was released. The hearing marked the third time Xu’s request for bond was denied.

Annamartine Salick, deputy chief of the Terrorism and Export Crime Section of the US Attorney’s office in Los Angeles and the lead prosecutor on the case against Xu, declined comment.

In a court filing, she cited Xu’s “litany of lies and contempt for the rule of law” as among the reasons he should be denied bond.

Jack Weiss, a former federal prosecutor in Los Angeles who now runs an investigative firm, said the allegations against Xu are especially troubling given his role in law enforcement.

“This is someone you would never want in a position of authority in the US government,” Weiss said. “I imagine there is going to be some kind of internal review as to how it is that he was wearing a badge.”

Born in China, Xu came to the United States on a student visa in the late 1980s. He became a naturalized citizen in 1999. In 2004, following stints in the private sector as an engineer and entrepreneur, he was hired by Customs and Border Protection — a job requiring a secret-level security clearance subject to periodic renewals.

Prior to his arrest in February, Xu worked as a watch commander for CBP at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

Jaime Ruiz, a spokesman for US Customs and Border Protection, said Xu is now on “indefinite suspension.”

According to prosecutors, Xu repeatedly made false statements and concealed information when he filled out questionnaires for his security clearance under penalty of perjury.

Among other things, prosecutors said, Xu failed to disclose his ownership of two companies that do business with China and his “extensive business contacts with Chinese nationals.”

Agents say they found evidence of a bank account in China in the trash outside Xu’s home and recovered two copies of Chinese passports, bearing the name Wei Xu but featuring photos of other people, from Xu’s desk.

Salick argued at one of Xu’s detention hearings that she’d been told by CBP officers that if Xu falsely claimed to have lost his own passport, he could pretend to be one of the Chinese citizens bearing his name, provide that man’s biographical information to the Chinese consulate, and would likely be issued travel documents to return to China.

Following Xu’s arrest, investigators learned of his “long-standing contact with members of the Consulate General of the People’s Republic of China in Los Angeles,” according to court records.

Agents seized emails, texts and phone records showing that Xu had been communicating with consular officials since at least 2013, according to court records. He was invited to events hosted by the consulate in 2017 and 2018, the records state, and agents reviewed images on his cell phone “appearing to show” that Xu and his wife attended the events.

Attempts to reach Chinese consular officials in Los Angeles were not immediately successful.

Werksman downplayed his client’s purported wealth in a brief interview with CNN, saying, for example, that the Maserati was leased. He said Xu’s companies exported forklift parts and generated limited income. He said the Chinese bank account authorities discovered was opened 20 years ago and contained the relatively meager sum of $1,700.

He also dismissed any intrigue surrounding Xu’s ties to China.

He said in a court filing that the photocopies of passports seized from his office were placed there by co-workers playing a prank on Xu, whose duties include overseeing entry and exit of Chinese vessels in San Pedro, and who was at one point investigating two men who had the same — very common — first and last name that he did.

He said Xu’s contact with consular officials was related to his work at the port, in which he sometimes contacted the consulate about crewmembers on Chinese ships who were seeking asylum in the United States.

“There’s nothing nefarious about it,” he told CNN.

It was while investigating Xu regarding his security clearance that agents discovered his alleged involvement in the illegal gun trade.

In the summer of 2017, FBI agents say they retrieved a spreadsheet listing online accounts and login information from the trash outside Xu’s home. Two of the accounts pertained to a website that acts as a marketplace for private gun sales.

An undercover agent with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives began corresponding with Xu and eventually purchased four guns.

In one transaction in July, Xu showed up in a 2016 Maserati with an assault rifle in the trunk, according to prosecutors.

The undercover agent commented on the black sedan before giving Xu $1,600 cash for the rifle.

“I’m like you, playboy,” Xu allegedly responded.

Following another deal, in which Xu allegedly sold the agent a rifle and five high-capacity magazines for $2,100, the CBP officer quipped, “We are like drug dealers,” according to a search warrant affidavit.

Werksman described his client as a “nerdy engineer” who collected firearms as a hobby and had no intention of becoming a gun dealer.

“He comes home from work, goes out to the garage and tinkers with guns,” the lawyer said. “He wasn’t going to hurt anyone.”